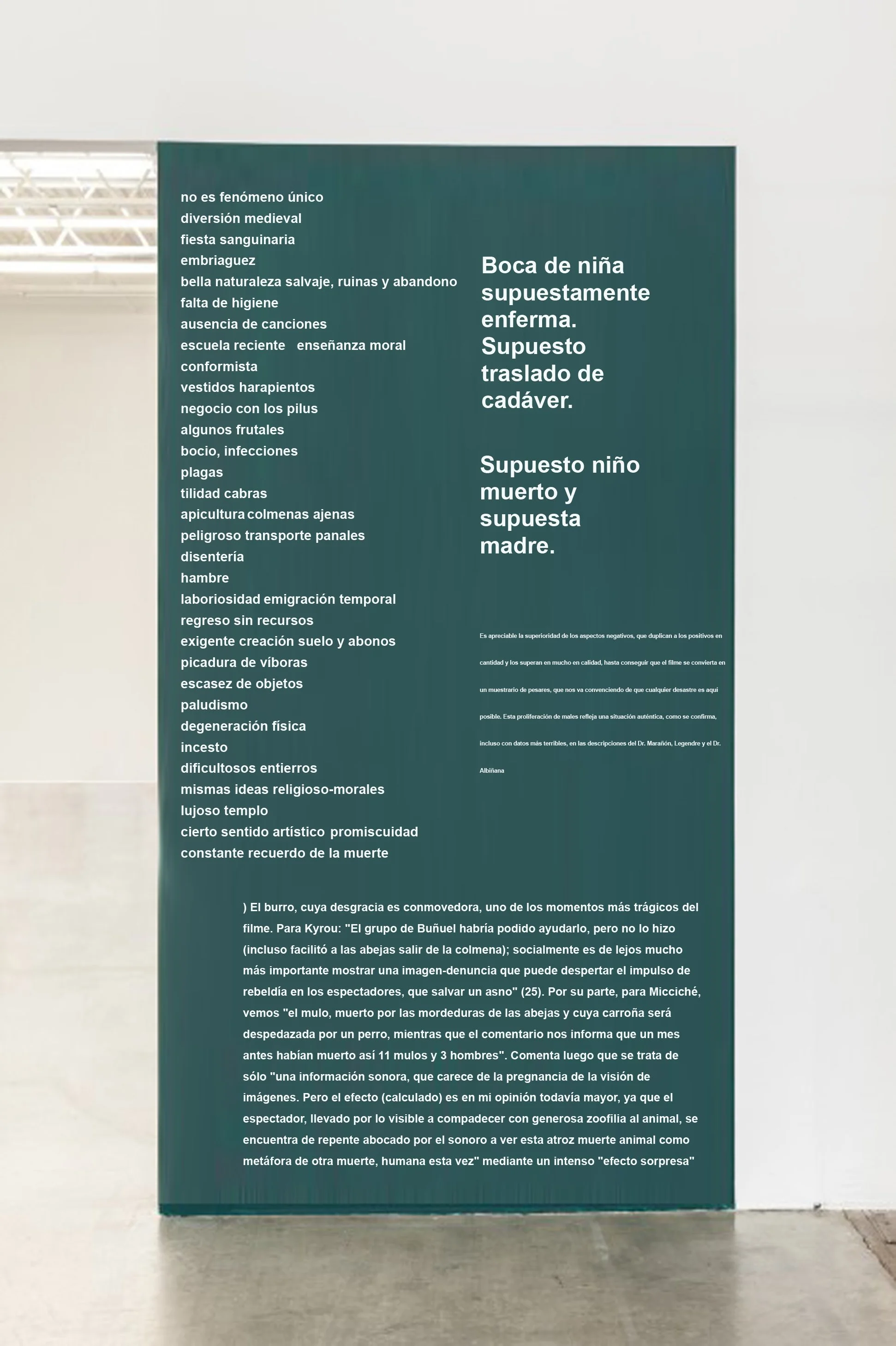

La imagen y su doble | The Image and its Double, 2015

Enameled on wall. 400 x 180 cm

Installation views, CCE Santiago 2015

La imagen y su doble | The Image and its Double, 2015

Enameled on wall. 400 x 180 cm

Installation views, CCE Santiago 2015